1.1. Studying more-than-human ecologies

Humans have played a key role in the management of African landscapes for more than two million years (Adams and McShane 199228). During this time local people have nurtured sophisticated relationships with wildlife and developed practices, techniques and belief systems built upon rich knowledge about the environments in which they live, in order to sustain rural livelihoods and maintain an ecological and spiritual balance with the natural world (Paré et al. 201029).

Studies which explore more-than-human ecologies are broad and encompass multiple and diverse disciplines and topics. They include the use and harvest of natural resources by humans and sympatric species (Duvall 200730; Humle and Matsuzawa 200431; Pruetz et al. 200232); local cultural beliefs surrounding other-than-humans; conflict, coexistence and wildlife classification (Assogbadjo et al. 200833; Bowker and Star 200034; Ellen and Reason 197935; Friese 201036; Galhano Alves 200937; Hockings 200938; Hockings et al. 201039; Horton 196740; Larson et al. 201641; Lee and Graham 200642); disease transmission (Funk et al. 201343; Subramanian 201244); hunting (Amador et al. 201445; Bowen-Jones et al. 200346); community conservation (Baran and Tous 200047; Conway et al. 201548; Nyanganji et al. 201149; Sousa et al. 201450); the impacts of global policy on conservation agendas (Adams and McShane 199228; Kiss 199051; Oates 199952; Moyo 200953; Pearson et al. 199154); the effects of migration, media, religion, identity, education and tourism on local culture and ecologies (Bordonaro 200655; Lundy 201556, 201257); the role of humans, plants and animals in multispecies ‘life-worlds’ (Johnston 200858; Wilbert 200059; Wolch and Emel 199560); and the resilience of more-than-human communities in the face of ecological and cultural change (Frazão-Moreira 201661; Hockings and Sousa 201162; Lundy 201556). In West Africa more-than-human relationships have been examined by anthropologists, interested in how environments are cultivated and managed by local people and the role of cultural and religious beliefs and practices on the local ecology (Bassett and Zuéli 200063; Duvall 200364; Houehanou et al. 201165; Kristensen and Lykke 200366; Norris et al. 201067;Paré et al. 201029, Tabuti and Mugula 200768; Temudo and Cabral 201769; Wilbanks and Kates 199970). This research is timely and important as it demonstrates the complexity of multispecies ecologies, contributing valuable data to conservation (e.g. Hockings et al. 202071).

Understanding the impact of more-than-humans on landscapes, ecologies and communities is vital to minimising and responding to environmental changes and their social, political and economic impact. It draws attention to the diverse and conflicting goals of different interest groups and how these ideals play out; providing valuable information in terms of understanding complex multi-actor networks (specifically those involved in wildlife management and biological conservation). A prime example of this is the controversial debate over the bushmeat trade - which is recognised as a major contributor to the depletion of African forests (Bennett et al. 200772; Bowen-Jones and Pendry 199973; Lindsey et al 201374; Peterson 200375) but also as a major food source, a primary source of income and an important cultural practice for many rural African communities. Indepth socio-economic studies exploring bushmeat consumption in West Africa have identified this trade as a key contributor to the economy with rural people making rational choices about hunting based on the price of ammunition, the distance between villages, the size of the animal and the need for food and cash (Adams and McShane 199228 in Liberia; Bowen-Jones et al. 200376 in Gabon). However, on-going efforts to conserve wildlife and provide food security for local communities have seen the introduction of agricultural practices imposed by aid agencies which have repeatedly exacerbated forest decline and failed to produce sustainable results (Garrity et al. 201077). Anthropologists, on-the-other-hand, have examined the social and cultural significance of hunting practices and explored viable alternatives which would enable communities to continue to bring in an income whilst also meeting their nutritional needs (Adams and McShane 199228; Sá et al 201278).

The documentation of multispecies relationships generates a narrative which describes ambiguous species and social boundaries and nurtures a holistic ecological research approach. These ideas often reflect the worldview of communities living in proximity to nature (Descola 199479; Ingold 201380; Kohn 201381; Corrigan et al. 201882)and therefore provide a means through which to implement conservation from a grounded localised starting point (Parathian et al. 201883). In reality, however, local people are informed by a combination of beliefs and practices derived from traditional and contemporary ontologies in order to meet their everyday needs. Take for example the Nalú people in rural Guinea-Bissau, who establish practices of “resilience rather than rupture” by merging pre-Islamic and Islamic beliefs in their everyday lives and healing practices (Frazão-Moreira 201661). Similarly, the Bijagós people living in coastal Guinea-Bissau demonstrate high levels of resilience through “a complex web of multiethnic alliances, social linkages and political ties” (Forrest 2003:28, in Lundy 201556). Research suggests that these communities are continually seeking a balance between maintaining a sense of self and cultural cohesion, whilst existing within the constant flux and negotiation of a changing environment (Lundy 201556).

28. Adams, J. S., & McShane, T. O. (1992). The myth of wild Africa: conservation without illusion. University of California Press.

29. Paré, S., Savadogo, P., Tigabu, M., Ouadba, J. M. & Odén, P. C. (2010). Consumptive values and local perception of dry forest decline in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Pare.

30. Duvall, C. S. (2007). Human settlement and baobab distribution in south‐western Mali. Journal of Biogeography 34(11), 1947-1961.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4640660#metadata_info_tab_contents

31. Humle, T., & Matsuzawa, T. (2004). Oil palm use by adjacent communities of chimpanzees at Bossou and Nimba mountains, West Africa. International Journal of Primatology 25, 551–581.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:IJOP.0000023575.93644.f4

32. Pruetz, J. D., Marchant, L. F., Arno, J., & McGrew, W. C. (2002). Survey of savanna chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in southeastern Senegal. American Journal of Primatology: Official Journal of the American Society of Primatologists, 58(1), 35-43.

https://erinwessling.com/publication/ndiaye_2018/

33. Assogbadjo, A. E., Kakaï, R. G., Chadare, F. J., Thomson, L., Kyndt, T., Sinsin, B., & Van Damme, P. (2008). Folk classification, perception, and preferences of baobab products in West Africa: consequences for species conservation and improvement. Economic botany 62(1), 74-84.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12231-007-9003-6

34. Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (2000). Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. MIT Press.

https://direct.mit.edu/books/book/4738/Sorting-Things-OutClassification-and-Its

35. Ellen, R. F., & Reason, D. (eds). (1979). Classifications in their social context. New York: Academic Press.

36. Friese, C. (2010). Classification conundrums: categorizing chimeras and enacting species preservation. Theory and Society 39(2), 145-172.

37. Galhano Alves, J.P. (2009). Viver com leões. A coexistência entre humanos e biodiversidade no W do Níger. Os Gourmantché, Trabalhos de Antropologia e Etnologia, Sociedade Portuguesa de Antropologia e de Etnologia 49(1-4), 57-77.

https://revistataeonline.weebly.com/uploads/2/2/0/2/22023964/viver_joaoalves_tae49.pdf

38. Hockings, K. J. (2009). Living at the interface: human–chimpanzee competition, coexistence and conflict in Africa. Interaction Studies 10(2), 183-205.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233627028_Living_at_the_interface_Human-chimpanzee_competition_coexistence_and_conflict_in_Africa

39. Hockings, K. J., Yamakoshi, G., Kabasawa, A., & Matsuzawa, T. (2010). Attacks on local persons by chimpanzees in Bossou, Republic of Guinea: long‐term perspectives. American Journal of Primatology 72(10), 887-896.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajp.20784

40. Horton, R. (1967). African traditional thought and western science. From tradition to science. Part I. Africa, 50-71.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1157195#metadata_info_tab_contents

41. Larson, L. R., April L. Conway, S. M. Hernandez, & Carroll, J. P. (2016) Human-wildlife conflict, conservation attitudes, and a potential role for citizen science in Sierra Leone, Africa. Conservation and Society 14(3), 205.

https://www.conservationandsociety.org.in/article.asp?issn=0972-4923;year=2016;volume=14;issue=3;spage=205;epage=217;aulast=Larson

42. Lee, P. C. & M. D. Graham. (2006). African elephants (Loxodonta africana) and human-elephant interactions: implications for conservation. International Zoo Yearbook 40(1), 229-248.

https://zslpublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1748-1090.2006.00009.x

43. Funk, S., Nishiura, H., Heesterbeek, H., Edmunds, W. J., & Checchi, F. (2013). Identifying transmission cycles at the human-animal interface: the role of animal reservoirs in maintaining gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Comput Biol, 9(1), e1002855.

https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002855#s4

44. Subramanian, M. (2012). Zoonotic disease risk and the bushmeat trade: assessing awareness among hunters and traders in Sierra Leone. EcoHealth 9(4), 471-482.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10393-012-0807-1

45. Amador, R., Casanova, C., & Lee, P. (2014). Ethnicity and perceptions of bushmeat hunting inside Lagoas de Cufada Natural Park (LCNP), Guinea-Bissau. Journal of Primatology 3(121), 1-8.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276314826_Ethnicity_and_Perceptions_of_Bushmeat_Hunting_Inside_Lagoas_de_Cufada_Natural_Park_LCNP_Guinea-Bissau

46. Bowen‐Jones, E., Brown, D., & Robinson, E. J. (2003). Economic commodity or environmental crisis? An interdisciplinary approach to analysing the bushmeat trade in central and west Africa. Area 35(4), 390-402.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20004344#metadata_info_tab_contents

47. Baran, E. & Tous, P. (2000). Artisanal fishing, sustainable development and co-management of resources: Analysis of a successful project in West Africa. IUCN.

https://www.iucn.org/content/artisanal-fishing-sustainable-development-and-co-management-resources-analysis-a-successful-project-west-africa-0

48. Conway, A. L., Hernandez, S. M., Carroll, J. P., Green, G. T., & Larson, L. (2015). Local awareness of and attitudes towards the pygmy hippopotamus Choeropsis liberiensis in the Moa River Island Complex, Sierra Leone. Oryx 49(3), 550-558.

https://www.academia.edu/33624823/Local_awareness_of_and_attitudes_towards_the_pygmy_hippopotamus_Choeropsis_liberiensis_in_the_Moa_River_Island_Complex_Sierra_Leone

49. Nyanganji, G., Fowler, A., McNamara, A., & Sommer, V. (2011). Monkeys and apes as animals and humans: ethno-primatology in Nigeria’s Taraba region. In Primates of Gashaka. Pp. 101-134. Springer, New York, NY.

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4419-7403-7_4

50. Sousa, J., Vicente, L., Gippoliti, S., Casanova, C., & Sousa, C. (2014). Local knowledge and perceptions of chimpanzees in Cantanhez National Park, Guinea‐Bissau. American Journal of Primatology 76(2): 122-134.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257755400_Local_Knowledge_and_Perceptions_of_Chimpanzees_in_Cantanhez_National_Park_Guinea-Bissau

51. Kiss, A. (1990). Living with wildlife: wildlife resource management with local participation in Africa. The World Bank.

https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/247611468742847173/living-with-wildlife-wildlife-resource-management-with-local-participation-in-africa

52. Oates, J. F. (1999). Myth and reality in the rain forest: how conservation strategies are failing in West Africa. University of California Press.

53. Moyo, D. (2009). Dead aid: Why aid is not working and how there is a better way for Africa. Macmillan.

54. Pearson, S. R., Stryker, J. D., & Humphreys, C. P. (1981). Rice in West Africa: policy and economics. Stanford University Press.

https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNABB800.pdf

55. Bordonaro, L. I. (2006). Living at the Margins: Youth and the Global in Bubaque (Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau). PhD Thesis in Anthropology. Lisbon. ISCTE.

https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/348/1/Bordonaro%202006_Living%20at%20the%20Margins.pdf

56. Lundy. B. D. (2015). Resistance is Fruitful: Bijagós of Guinea-Bissau. Peace and Conflict Management Working Paper 1, 1-9.

https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=working_papers_ccm

57. Lundy, B. D. (2012). Playing the Market: How the Cashew “Commodityscape” Is Redefining Guinea-Bissau's Countryside. CAFÉ 34, 33–52. doi:10.1111/j.2153-9561.2012.01063.x

https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2153-9561.2012.01063.x~

58. Johnston, C. (2008). Beyond the clearing: towards a dwelt animal geography. Progress in human geography 32(5), 633-649.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0309132508089825

59. Wilbert, C. (2000). Anti-this, against that, resistances along a human–nonhuman axis. In: J. Sharp, P. Routledge, C. Philo and R. Paddeston(eds). Entanglements of power- geographies of domination/resistance. London: Routledge. Pp. 238–55.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335193028_Wilbert_C_2000_'Anti-this_-_Against-that_resistances_along_a_human-non-human_axis'

60. Wolch, J. & Emel, J. (1995). Bringing the animals back in. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 13(6), 632–6.

https://journals.sagepub.com/toc/epd/13/6

61. Frazão-Moreira, A. (2016). The symbolic efficacy of medicinal plants: practices, knowledge, and religious beliefs amongst the Nalu healers of Guinea-Bissau. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine 12(24), 1-15.

https://ethnobiomed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13002-016-0095-x

62. Hockings, K. J., & Sousa. C. (2011). Human-Chimpanzee Sympatry and Interactions in Cantanhez National Park, Guinea- Bissau: Current Research and Future Directions. Primate Conservation 26, 1-9.

https://bioone.org/journals/primate-conservation/volume-26/issue-1/052.026.0104/Human-Chimpanzee-Sympatry-and-Interactions-in-Cantanhez-National-Park-Guinea/10.1896/052.026.0104.full

63. Bassett, T. J., & Zuéli, K. B. (2000). Environmental discourses and the Ivorian savanna. Annals of the Association of American Geographers90(1), 67-95.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/0004-5608.00184

64. Duvall, C. S. (2003). Symbols, not data: rare trees and vegetation history in Mali. Geographical Journal 169(4), 295-312.

https://www.academia.edu/5482169/Symbols_not_data_rare_trees_and_vegetation_history_in_Mali

65. Houehanou, T. D., Assogbadjo, A. E., Kakaï, R. G., Houinato, M., & Sinsin, B. (2011). Valuation of local preferred uses and traditional ecological knowledge in relation to three multipurpose tree species in Benin (West Africa). Forest Policy and Economics, 13(7), 554-562.

https://www.academia.edu/14337292/Valuation_of_local_preferred_uses_and_traditional_ecological_knowledge_in_relation_to_three_multipurpose_tree_species_in_Benin_West_Africa_

66. Kristensen, M., & Lykke, A. M. (2003). Informant-based valuation of use and conservation preferences of savanna trees in Burkina Faso. Economic Botany, 57(2), 203-217.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0203:IVOUAC]2.0.CO;2

67. Norris, K., Asase, A., Collen, B., Gockowksi, J., Mason, J., Phalan, B., & Wade, A. (2010). Biodiversity in a forest-agriculture mosaic – The changing face of West African rainforests. Biological conservation 143(10), 2341-2350.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0203:IVOUAC]2.0.CO;2

68. Tabuti, J. R., & Mugula, B. B. (2007). The ethnobotany and ecological status of Albizia coriaria Welw. ex Oliv. in Budondo Sub‐county, eastern Uganda. African Journal of Ecology, 45, 126-129.

https://www.academia.edu/2554335/The_ethnobotany_and_ecological_status_of_Albizia_coriaria_Welw_ex_Oliv_in_Budondo_Sub_county_eastern_Uganda

69. Temudo, M. P., & Cabral, A. I. (2017). The social dynamics of mangrove forests in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Human Ecology, 45(3), 307-320.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-017-9907-4

70. Wilbanks, T. J. & Kates, R. (1999). Global Changes in Local Places: How Scale Matters. Climatic Change 43:601-628.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1005418924748

71. Hockings, K. J., Parathian, H. E., Bessa, J., & Frazão-Moreira, (2020). A. Extensive overlap in the selection of wild fruits by chimpanzees and humans: Implications for the management of complex social-ecological systems. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8, 123.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2020.00123/full

72. Bennett, E. L., Blencowe, E., Brandon, K., Brown, D., Burn, R. W., Cowlishaw, G. et al. (2007). Hunting for consensus: reconciling bushmeat harvest, conservation, and development policy in West and Central Africa. Conservation Biology 21(3), 884-887.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4620885#metadata_info_tab_contents

73. Bowen‐Jones, E., & Pendry, S. (1999). The threat to primates and other mammals from the bushmeat trade in Africa, and how this threat could be diminished 1. Oryx 33(3), 233-246.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/oryx/article/threat-to-primates-and-other-mammals-from-the-bushmeat-trade-in-africa-and-how-this-threat-could-be-diminished/B82AF6A280E5A9BF029EFB9872DEBCCD

74. Lindsey, P. A., Balme, G., Becker, M., Begg, C., Bento, C., Bocchino, C. et al. (2013). The bushmeat trade in African savannas: Impacts, drivers, and possible solutions. Biological Conservation, 160, 80-96.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320712005186

75. Peterson, D. (2003). Eating apes (Vol. 6). University of California Press.

76. Bowen‐Jones, E., Brown, D., & Robinson, E. J. (2003). Economic commodity or environmental crisis? An interdisciplinary approach to analysing the bushmeat trade in Central and West Africa. Area 35(4), 390-402.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20004344#metadata_info_tab_contents

77. Garrity, D.P., Akinnifesi, F.K., Ajayi, O.C., Weldesemayat, S.G., Mowo, J.G., Kalinganire, A., Larwanou, M. & Bayala, J. (2010). Evergreen Agriculture: a robust approach to sustainable food security in Africa. Food security 2(3), 197-214.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12571-010-0070-7

78. Sá, R., Ferreira da Silva, M., Sousa, F., & Minhós, T. (2012). The trade and ethnobiological use of chimpanzee body parts in Guinea-Bissau: implications for conservation. Traffic Bulletin 24(1), 31.

https://www.academia.edu/1257921/The_Trade_and_Ethnobiological_Use_of_Chimpanzee_Body_Parts_in_Guinea_Bissau_Implications_for_Conservation

79. Descola P. (1994). In the society of nature: A native ecology in Amazonia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

80. Ingold, T. (2013). Anthropology beyond Humanity. Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society 38(3), 5-23.

https://www.waunet.org/downloads/wcaa/dejalu/feb_2015/ingold.pdf

81. Kohn, E. (2013). How Krensky, S. 2007. Ananse and the Box of Stories: A West African Folktale. Millbrook Press. Pp. 48.

82. Corrigan, C., Bingham, H., Shi, Y., Lewis, E., Chauvenet, A., & Kingston, N. (2018). Quantifying the contribution to biodiversity conservation of protected areas governed by indigenous peoples and local communities. Biological Conservation, 227, 403-412.

83. Parathian, H. E., McLennan, M. R., Hill C. M., Frazão–Moreira A. & Hockings, K.J. (2018). Breaking through disciplinary barriers: human–wildlife interactions and multispecies ethnography. International Journal of Primatology. Special Issue: Primatology in the 21st Century 39(5),1-27.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10764-018-0027-9

https://ethnobiomed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13002-016-0095-x

62. Hockings, K. J., & Sousa. C. (2011). Human-Chimpanzee Sympatry and Interactions in Cantanhez National Park, Guinea- Bissau: Current Research and Future Directions. Primate Conservation 26, 1-9.

https://bioone.org/journals/primate-conservation/volume-26/issue-1/052.026.0104/Human-Chimpanzee-Sympatry-and-Interactions-in-Cantanhez-National-Park-Guinea/10.1896/052.026.0104.full

63. Bassett, T. J., & Zuéli, K. B. (2000). Environmental discourses and the Ivorian savanna. Annals of the Association of American Geographers90(1), 67-95.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/0004-5608.00184

64. Duvall, C. S. (2003). Symbols, not data: rare trees and vegetation history in Mali. Geographical Journal 169(4), 295-312.

https://www.academia.edu/5482169/Symbols_not_data_rare_trees_and_vegetation_history_in_Mali

65. Houehanou, T. D., Assogbadjo, A. E., Kakaï, R. G., Houinato, M., & Sinsin, B. (2011). Valuation of local preferred uses and traditional ecological knowledge in relation to three multipurpose tree species in Benin (West Africa). Forest Policy and Economics, 13(7), 554-562.

https://www.academia.edu/14337292/Valuation_of_local_preferred_uses_and_traditional_ecological_knowledge_in_relation_to_three_multipurpose_tree_species_in_Benin_West_Africa_

66. Kristensen, M., & Lykke, A. M. (2003). Informant-based valuation of use and conservation preferences of savanna trees in Burkina Faso. Economic Botany, 57(2), 203-217.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0203:IVOUAC]2.0.CO;2

67. Norris, K., Asase, A., Collen, B., Gockowksi, J., Mason, J., Phalan, B., & Wade, A. (2010). Biodiversity in a forest-agriculture mosaic – The changing face of West African rainforests. Biological conservation 143(10), 2341-2350.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0203:IVOUAC]2.0.CO;2

68. Tabuti, J. R., & Mugula, B. B. (2007). The ethnobotany and ecological status of Albizia coriaria Welw. ex Oliv. in Budondo Sub‐county, eastern Uganda. African Journal of Ecology, 45, 126-129.

https://www.academia.edu/2554335/The_ethnobotany_and_ecological_status_of_Albizia_coriaria_Welw_ex_Oliv_in_Budondo_Sub_county_eastern_Uganda

69. Temudo, M. P., & Cabral, A. I. (2017). The social dynamics of mangrove forests in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Human Ecology, 45(3), 307-320.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-017-9907-4

70. Wilbanks, T. J. & Kates, R. (1999). Global Changes in Local Places: How Scale Matters. Climatic Change 43:601-628.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1005418924748

71. Hockings, K. J., Parathian, H. E., Bessa, J., & Frazão-Moreira, (2020). A. Extensive overlap in the selection of wild fruits by chimpanzees and humans: Implications for the management of complex social-ecological systems. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8, 123.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2020.00123/full

72. Bennett, E. L., Blencowe, E., Brandon, K., Brown, D., Burn, R. W., Cowlishaw, G. et al. (2007). Hunting for consensus: reconciling bushmeat harvest, conservation, and development policy in West and Central Africa. Conservation Biology 21(3), 884-887.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4620885#metadata_info_tab_contents

73. Bowen‐Jones, E., & Pendry, S. (1999). The threat to primates and other mammals from the bushmeat trade in Africa, and how this threat could be diminished 1. Oryx 33(3), 233-246.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/oryx/article/threat-to-primates-and-other-mammals-from-the-bushmeat-trade-in-africa-and-how-this-threat-could-be-diminished/B82AF6A280E5A9BF029EFB9872DEBCCD

74. Lindsey, P. A., Balme, G., Becker, M., Begg, C., Bento, C., Bocchino, C. et al. (2013). The bushmeat trade in African savannas: Impacts, drivers, and possible solutions. Biological Conservation, 160, 80-96.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320712005186

75. Peterson, D. (2003). Eating apes (Vol. 6). University of California Press.

76. Bowen‐Jones, E., Brown, D., & Robinson, E. J. (2003). Economic commodity or environmental crisis? An interdisciplinary approach to analysing the bushmeat trade in Central and West Africa. Area 35(4), 390-402.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20004344#metadata_info_tab_contents

77. Garrity, D.P., Akinnifesi, F.K., Ajayi, O.C., Weldesemayat, S.G., Mowo, J.G., Kalinganire, A., Larwanou, M. & Bayala, J. (2010). Evergreen Agriculture: a robust approach to sustainable food security in Africa. Food security 2(3), 197-214.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12571-010-0070-7

78. Sá, R., Ferreira da Silva, M., Sousa, F., & Minhós, T. (2012). The trade and ethnobiological use of chimpanzee body parts in Guinea-Bissau: implications for conservation. Traffic Bulletin 24(1), 31.

https://www.academia.edu/1257921/The_Trade_and_Ethnobiological_Use_of_Chimpanzee_Body_Parts_in_Guinea_Bissau_Implications_for_Conservation

79. Descola P. (1994). In the society of nature: A native ecology in Amazonia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

80. Ingold, T. (2013). Anthropology beyond Humanity. Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society 38(3), 5-23.

https://www.waunet.org/downloads/wcaa/dejalu/feb_2015/ingold.pdf

81. Kohn, E. (2013). How Krensky, S. 2007. Ananse and the Box of Stories: A West African Folktale. Millbrook Press. Pp. 48.

82. Corrigan, C., Bingham, H., Shi, Y., Lewis, E., Chauvenet, A., & Kingston, N. (2018). Quantifying the contribution to biodiversity conservation of protected areas governed by indigenous peoples and local communities. Biological Conservation, 227, 403-412.

83. Parathian, H. E., McLennan, M. R., Hill C. M., Frazão–Moreira A. & Hockings, K.J. (2018). Breaking through disciplinary barriers: human–wildlife interactions and multispecies ethnography. International Journal of Primatology. Special Issue: Primatology in the 21st Century 39(5),1-27.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10764-018-0027-9

1.2. Ecological and community health

Today's era of globalisation is characterised by intensified interspecies encounters and growing concerns over ecological and species health (Rock et al. 200984; Wolf 201585). The uncertain futures of more-than-humans are entwined within complex socio-political hierarchies, large-scale habitat destruction and exposure to increasingly aggressive infectious disease. Contemporary human-animal relationships have been described as being “complex and profound”, ranging from the exploitation of livestock for food; the anthropomorphisation of animals as pets; live ‘wet markets’; and international trade in animal species, offering multiple opportunities for zoonoses to spread (Zinsstag et al. 2012:10786). There is mounting evidence to suggest that environmental degradation increases immunosuppression and susceptibility to disease, and that community health and wellbeing are inextricably linked to the health and balance of nature (The One Health Concept, Conti & Rabinowitz 201187). For example, biodiversity in West Africa is threatened by significant landscape changes due to agricultural expansion (with subsequent human migration), logging, mining and the trade in bushmeat and wild animals. These growing rates of deforestation and road construction facilitate accessibility to wildlife and an increased interface between human and animal populations which increases interspecies zoonotic disease transmission and facilitates the spread of sometimes deadly, novel viruses (Hughes et al. 201088; Subramanian 201289). Indeed, the current global (SARS-cov2) pandemic has led to global interest in understanding interspecies relationships and their emerging impact on ecological and community health (Zinsstag et al. 202090).

The trade in wild animals for medicinal and nutritional needs has been identified as a high-risk activity, likely to increase zoonotic disease transmission between humans and wildlife, whilst also highlighting the impact of socio-cultural variables on wildlife management (Alves et al. 201091). Therefore, adopting an interdisciplinary approach which delves into the social and cultural aspects of more-than-human interactions can generate vital information on existing knowledge structures which have evolved in-situ, underscoring the valuable contribution of ethnographic research to conservation planning and the consequential shortfalls of not considering local knowledge and perceptions when designing such programmes (ibid. 201091). Talking to local people and incorporating existing local strategies into wildlife management planning can provide insightful information about interspecies disease transmission, which saves time and resources and achieves far better long-term outcomes for people and wildlife. For example, during the introduction of Protected Areas (PAs) on the African continent in 1900s, some farmers and scientists objected, fearful the large numbers of wild animals would lead to the increased spread of disease through the high numbers of tsetse flies (Adams and McShane 199292). However, since well before the “official” launch of this scheme, local people had managed their landscapes, adopting practices based on indepth local knowledge and an understanding of the interplay between species, including zoonotic disease transmission. When the PA strategy was implemented local people adapted their own practices to ensure disease risk was minimised. They avoided areas known to be focal points of tsetse infection and made sure cattle ate young sprouts which prevented scrub growth and meant tsetse fly numbers remained low. Local hunting practices also helped reduce the spread of tsetse by regulating wildlife populations that could act as hosts for the flies. Profound local knowledge about these between-speciesinteractions meant local people implemented a sustainable mitigation strategy which supported “a mobile ecological equilibrium” to protect people and wildlife (ibid. 1992:48-4992).

84. Rock, M., Buntain, B. J., Hatfield, J. M., & Hallgrímsson, B. (2009). Animal–human connections,“one health,” and the syndemic approach to prevention. Social science & medicine, 68(6), 991-995.

https://www.academia.edu/en/12732482/Animal_human_connections_one_health_and_the_syndemic_approach_to_prevention

85. Wolf, M. (2015). Is there really such a thing as “One Health”? Thinking about a more than human world from the perspective of cultural anthropology. Social Science & Medicine 129, 5-11.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24961737/

86. Zinsstag, J. (2012). Convergence of ecohealth and one health, 371-373.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3627853/

87. Conti & Rabinowitz 2011. One health initiative. Infektološki glasnik 31(4):176-178.

https://hrcak.srce.hr/clanak/127454

88. Hughes, J.M., Wilson, M.E., Pike, B.L., Saylors, K.E., Fair, J.N., LeBreton, M., Tamoufe, U., Djoko, C.F., Rimoin, A.W. & Wolfe, N.D. (2010). The origin and prevention of pandemics. Clinical Infectious Diseases 50(12),1636-1640.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2874076/

89. Subramanian, M. (2012). Zoonotic disease risk and the bushmeat trade: assessing awareness among hunters and traders in Sierra Leone. EcoHealth 9(4), 471-482.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10393-012-0807-1

90. Zinsstag, J., Schelling, E., Crump, L., Whittaker, M., Tanner, M., & Stephen, C. (Eds.). (2020). One Health: the theory and practice of integrated health approaches, 2nd edition. Boston, Oxford: CABI.

https://cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/book/10.1079/9781789242577.0000

91. Alves, R., Souto, W., & Barboza, R. (2010). Primates in traditional folk medicine: a world overview. Mammal Review 40(2), 155-180.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2907.2010.00158.x

92. Adams, J. S., & McShane, T. O. (1992). The myth of wild Africa: conservation without illusion. University of California Press.

1.3. Local knowledge, beliefs and practices

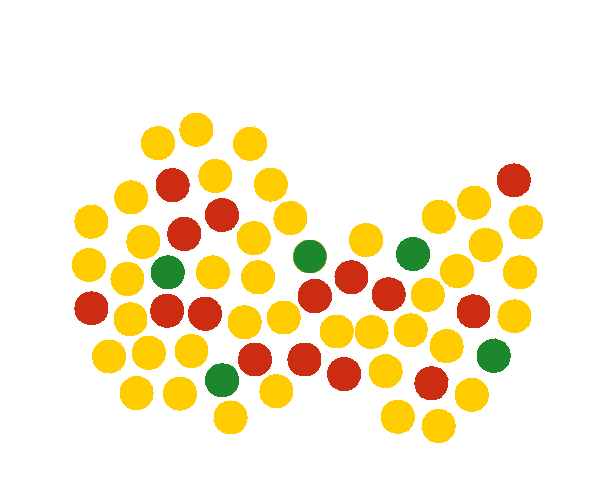

3. “Majidura” (prohibition, affected by magical-religious powers) signalling forbidden forest at the time of rite of passage for male age group. Bijagó, Guinea-Bissau. Photo: Amélia Frazão-Moreira.

Knowledge based upon experience gathered over generations and shaped by a combination of religious and cultural views means many local communities impose ecological checks and balances which guide local resource use and the maintenance of wild animal and plant species. Cultural mechanisms in African societies have proven effective in regulating wildlife abundance for over hundreds of years. These include taboos, sacred sites, traditional farming and medicinal practices, and values based on gender and status often relayed through folkstories from one generation to the next (Adams and McShane 199293; Baker et al. 200994; 201895; Decher 199796). Indeed, local resource use and wildlife management has emerged as a priority area of research for conservation and anthropology (Houehanou et al. 201197; Tabuti and Mugula 200798). For example, data on the utilisation of tree species by local people and local perceptions of forest change, have proven essential in developing effective sustainable management strategies in Central and Western Africa (Bassett and Zuéli 200099 in Côte d’Ivoire; Paré et al. 2010100 in Burkina Faso; Sousa et al. 2014101 in Guinea Bissau). This awareness is also at the root of successful local adaptation processes which have sustained interspecies relationships in the face of ecological, social and political change (Assogbadjo et al. 2008102; Baker et al. 2013103).

Another key source of understanding local ecological knowledge comes from the study of West African folkstories. These stories often communicate complex information about symbolic animals and between-species relationships. For example, The West African Story of ‘Anasi the Spider’ exists in various versions among the Dagaare-speaking people of north west Ghana. Linguists have discovered that each version has its own subtle lexical variations which set up specific systems of relationships between the words. This changes the storyteller’s connection to referents and ultimately conveys different messages to the listener (Dakubu 1990104). Understanding the true depth of material conveyed through traditional oral practices requires detailed analyses and can reveal important socio-ecological information and the value of local knowledge and the complexity of beliefs surrounding wildlife is increasingly becoming recognised (Assogbadjo et al. 2008102; Dakubu 1990104). This research is fast becoming an invaluable component of biodiversity conservation (Baran and Tous 2000105; Conway et al. 2015106), proving especially important in terms of working out how local strategies and adaptations can be adopted and applied on a global scale (Wilbanks and Kates 1999107).

93. Adams, J. S., & McShane, T. O. (1992). The myth of wild Africa: conservation without illusion. University of California Press.

94. Baker, L. R., Tanimola, A. A., Olubode, O. S., & Garshelis, D. L. (2009). Distribution and abundance of sacred monkeys in Igboland, southern Nigeria. American Journal of Primatology: Official Journal of the American Society of Primatologists 71(7), 574-586.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19408287/

95. Baker, L. R., Tanimola, A. A., & Olubode, O. S. (2018). Complexities of local culturalprotection in conservation: the case of an Endangered African primate and forest groves protected by social taboos. Oryx 52(2), 262-270.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/oryx/article/complexities-of-local-cultural-protection-in-conservation-the-case-of-an-endangered-african-primate-and-forest-groves-protected-by-social-taboos/88CD0EF04A65E6A226603F44D978A52D

96. Decher, J. (1997). Conservation, small mammals, and the future of sacred groves West Africa. Biodiversity & Conservation 6(7),1007-1026.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1018991329431

97. Houehanou, T. D., Assogbadjo, A. E., Kakaï, R. G., Houinato, M., & Sinsin, B. (2011). Valuation of local preferred uses and traditional ecological knowledge in relation to three multipurpose tree species in Benin (West Africa). Forest Policy and Economics, 13(7), 554-562.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389934111000918

98. Tabuti, J. R., & Mugula, B. B. (2007). The ethnobotany and ecological status of Albizia coriaria Welw. ex Oliv. in Budondo Sub‐county, eastern Uganda. African Journal of Ecology, 45, 126-129.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2007.00869.x

99. Bassett, T. J., & Zuéli, K. B. (2000). Environmental discourses and the Ivorian savanna. Annals of the Association of American Geographers90(1), 67-95.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/0004-5608.00184

100. Paré, S., Savadogo, P., Tigabu, M., Ouadba, J. M. & Odén, P. C. (2010). Consumptive values and local perception of dry forest decline in Burkina Faso, West Africa.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10668-009-9194-3

101. Sousa, J., Vicente, L., Gippoliti, S., Casanova, C., & Sousa, C. (2014). Local knowledge and perceptions of chimpanzees in Cantanhez National Park, Guinea‐Bissau. American Journal of Primatology 76(2): 122-134.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajp.22215

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389934111000918

98. Tabuti, J. R., & Mugula, B. B. (2007). The ethnobotany and ecological status of Albizia coriaria Welw. ex Oliv. in Budondo Sub‐county, eastern Uganda. African Journal of Ecology, 45, 126-129.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2007.00869.x

99. Bassett, T. J., & Zuéli, K. B. (2000). Environmental discourses and the Ivorian savanna. Annals of the Association of American Geographers90(1), 67-95.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/0004-5608.00184

100. Paré, S., Savadogo, P., Tigabu, M., Ouadba, J. M. & Odén, P. C. (2010). Consumptive values and local perception of dry forest decline in Burkina Faso, West Africa.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10668-009-9194-3

101. Sousa, J., Vicente, L., Gippoliti, S., Casanova, C., & Sousa, C. (2014). Local knowledge and perceptions of chimpanzees in Cantanhez National Park, Guinea‐Bissau. American Journal of Primatology 76(2): 122-134.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajp.22215

102. Assogbadjo, A. E., Kakaï, R. G., Chadare, F. J., Thomson, L., Kyndt, T., Sinsin, B., & Van Damme, P. (2008). Folk classification, perception, and preferences of baobab products in West Africa: consequences for species conservation and improvement. Economic botany 62(1), 74-84.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12231-007-9003-6

103. Baker, L. R., Tanimola, A. A., Olubode, O. S. & Garshelis, D. L. (2013). Links between Local Folklore and the Conservation of Sclater's Monkey (Cercopithecus sclateri) in Nigeria. African Primates 8, 17-24.

http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/1200343/24024157/1386366906917/African+Primates+8+Baker.pdf?token=qsQPWiQU2fH5uBv4OQAREwRKRJc%3D

104. Dakubu, M. E. K. D., (1990). Why Spider is King of Stories: The Message in the Medium of a West African Tale. African Languages and Cultures 3(1), 33-56.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1771741#metadata_info_tab_contents

105. Baran, E. & Tous, P. (2000). Artisanal fishing, sustainable development and co-management of resources: Analysis of a successful project in West Africa. IUCN.

https://www.iucn.org/resources/publication/artisanal-fishing-sustainable-development-and-co-management-resources

106. Conway, A. L., Hernandez, S. M., Carroll, J. P., Green, G. T., & Larson, L. (2015). Local awareness of and attitudes towards the pygmy hippopotamus Choeropsis liberiensis in the Moa River Island Complex, Sierra Leone. Oryx 49(3), 550-558.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/oryx/article/local-awareness-of-and-attitudes-towards-the-pygmy-hippopotamus-choeropsis-liberiensis-in-the-moa-river-island-complex-sierra-leone/2EF0726E3E8752AFB6A24FEAD207A537

107. Wilbanks, T. J. & Kates, R. (1999). Global Changes in Local Places: How Scale Matters. Climatic Change 43:601-628.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1005418924748

1.4. Multispecies coexistence in Anthropogenic landscapes

For non-human species, survival in the so-called “Anthropocene” has meant adapting to changes brought about by large-scale human activity. Subsequently, there has been a gradual shift towards research which focuses on the impact of human actions in the natural world and the political arena of conservation biology, where plants and animals are treated as “resources” or “commodities” (Schmidt et al. 2016108; Sullivan 2013109; Wenzel 1991110), and integrated assessments of multispecies ecologies (recording climate, culture, populations, economies, governments, institutions and societal behaviour) inform our understanding of the implications of environmental change (Bassett and Zuéli 2000111; Paré et al. 2010112). In certain situations, plants and animals demonstrate incredible abilities to adapt and survive change, with humans and wildlife coexisting in relative harmony (Hockings et al. 2012113, 2015114 for apes; Humle and Matzuzawa 2004115 for chimpanzees in Bossou and Nimba; Padonou et al. 2015116 for plants in Guinea). Human-wildlife conflict or between-species aggression typically surfaces as a result of heightened competition over limited resources including food, space and water, or where outside intervention (such as development, tourism and conservation initiatives) does not take into account the needs of people and wildlife (Galhano Alves 2009117; Hockings et al. 2010118; Klailova et al. 2010119; Pruetz et al. 2002120). Hockings and colleagues (2010)118 have shown that chimpanzee attacks in Bossou, Guinea, mainly occurred during months of low wild fruit availability, where chimpanzees used narrow roads to access cultivated areas when seeking out alternative high-quality foods. Similarly, Zehnle (2015)121 reported exacerbated tensions between humans and leopards in the tropical forests of colonial Africa (Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Gabun and the Congo). Leopards, colonials, locals and other animals contended for space and bushmeat following a number political and environmental emergencies. Human attacks by leopards began to occur frequently, which led to leopard killings by people in order to protect themselves. Research suggests long-term interspecies relationships tend to exist where people tolerate wildlife because of cultural beliefs supporting their preservation (this is especially true for nonhuman primates in West Africa), such as the notion that chimpanzees are the ancestors of forest human communities and the forbidden killing of ‘sacred’ guenon species in Nigeria (Baker et al. 2013122; Hockings and Sousa 2012123; Sousa and Frazão-Moreira 2010124; Sousa et al. 2017125).

The multifaceted relationships of more-than-humans alongside indepth knowledge about wildlife among people living in proximity to nature demonstrates the significant role of wildlife in people’s lives (Mullin 2002126; Nance and Colby 2015127; Trautmann 2015128). Recognising this, researchers are increasingly exploring the more-than-human dimensions of social life, landscape history and animal geographies (Cohen and Odhiambo 1989129; Haraway 2008130; Johnston 2008131) and the study of multispecies relationships is becoming a fast-growing and exciting area of contemporary research (Wolch and Emel 1995132). In her ground-breaking essay on fungi Tsing (2012133) describes the intimate and intriguing interspecies companionship between fungi, humans, dead and live animals and plants. She suggests that the creation of plantations (which thrived as a result of forced control, slavery and conquest) shaped how contemporary agribusiness is organised including racial separation and the separation of people from their crops, the land and nature in general. Humans are a part of the entangled webs of nature (such as those formed by fungi and rhizomes) and yet human exceptionalism has blinded us from the fact that Human nature itself is an interspecies relationship. Tsing encourages us to move away from human-centric thinking and towards an Anthropology which places more-than-humans in the centre.

108. Schmidt, S., Manceur, A. M. & Seppelt, R. (2016). Uncertainty of Monetary Valued Ecosystem Services - Value Transfer Functions for Global Mapping. PLOS ONE 11(3):e0148524.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0148524

109. Sullivan, S. 2013. Banking nature? The spectacular financialisation of environmental conservation. Antipode 45(1):198-217.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.00989.x

110. Wenzel, G. (1991). Animal Rights. Human Rights: Ecology, Economy and Ideology in the Canadian Arctic. University of Toronto Press.

111. Bassett, T. J., & Zuéli, K. B. (2000). Environmental discourses and the Ivorian savanna. Annals of the Association of American Geographers90(1), 67-95.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/0004-5608.00184

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/0004-5608.00184

112. Paré, S., Savadogo, P., Tigabu, M., Ouadba, J. M. & Odén, P. C. (2010). Consumptive values and local perception of dry forest decline in Burkina Faso, West Africa.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10668-009-9194-3

113. Hockings, K.J., Anderson, J.R. & Matsuzawa, T. (2012). Socioecological adaptations by chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, inhabiting an anthropogenically impacted habitat. Animal Behaviour 83(3), 801-810.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347212000036

114. Hockings, K.J., McLennan, M.R., Carvalho, S., Ancrenaz, M., Bobe, R., Byrne, R.W., Dunbar, R.I., Matsuzawa, T., McGrew, W.C., Williamson, E.A. & Wilson, M.L. (2015). Apes in the Anthropocene: flexibility and survival. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 30(4), 215-222.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169534715000397

115. Humle, T., & Matsuzawa, T. (2004). Oil palm use by adjacent communities of chimpanzees at Bossou and Nimba mountains, West Africa. International Journal of Primatology 25, 551–581.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:IJOP.0000023575.93644.f4

116. Padonou, E. A., Teka, O., Bachmann, Y. Schmidt, M., Mette Lykke, A. & Sinsin, B. (2015). Using species distribution models to select species resistant to climate change for ecological restoration of bowé in West Africa. African Journal of Ecology 53:10.1111/aje.2015.53.issue-1, 83-92.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/aje.12205

117. Galhano Alves, J.P. (2009). Viver com leões. A coexistência entre humanos e biodiversidade no W do Níger. Os Gourmantché, Trabalhos de Antropologia e Etnologia, Sociedade Portuguesa de Antropologia e de Etnologia 49(1-4), 57-77.

https://revistataeonline.weebly.com/uploads/2/2/0/2/22023964/viver_joaoalves_tae49.pdf

118. Hockings, K. J., Yamakoshi, G., Kabasawa, A., & Matsuzawa, T. (2010). Attacks on local persons by chimpanzees in Bossou, Republic of Guinea: long‐term perspectives. American Journal of Primatology 72(10), 887-896.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajp.20784

119. Klailova, M., Hodgkinson, C., & Lee, P. C. (2010). Behavioral responses of one western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) group at Bai Hokou, Central African Republic, to tourists, researchers and trackers. American Journal of Primatology, 72(10), 897-906.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ajp.20829

120. Pruetz, J. D., Marchant, L. F., Arno, J., & McGrew, W. C. (2002). Survey of savanna chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in southeastern Senegal. American Journal of Primatology: Official Journal of the American Society of Primatologists, 58(1), 35-43.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ajp.10035

121. Zehnle, S. (2015). Of Leopards and Lesser Animals: Trials and Tribulations of the “Human-Leopard Murders” in Colonial Africa. In: S. Nance & J. Colby (eds). The Historical Animal. New York: Syracuse University Press. Pp. 221.

122. Baker, L. R., Tanimola, A. A., Olubode, O. S. & Garshelis, D. L. (2013). Links between Local Folklore and the Conservation of Sclater's Monkey (Cercopithecus sclateri) in Nigeria. African Primates 8, 17-24.

http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/1200343/24024157/1386366906917/African+Primates+8+Baker.pdf?token=qsQPWiQU2fH5uBv4OQAREwRKRJc%3D

123. Hockings, K. J., & Sousa, C. (2012). Differential utilization of cashew—a low-conflict crop—by sympatric humans and chimpanzees. Oryx 46(3), 375-381.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/oryx/article/differential-utilization-of-cashewa-lowconflict-cropby-sympatric-humans-and-chimpanzees/D430B80618B4927259DEB1FE4A02C72C

124. Sousa, C., & Frazão-Moreira, A. (2010). Etnoprimatologia ao serviço da conservação na Guiné-Bissau: o chimpanzé como exemplo. In Alves, A., Souto, F. & N. Peroni (eds.) Etnoecologia em perspectiva: natureza, cultura e conservação, Recife: NUPEEA, 187-200.

https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/10618/1/sousa_frazao-moreira_2010.pdf

125. Sousa, J., Hill, C. M. & Ainslie. A. (2017). Chimpanzees, sorcery and contestation in a protected area in Guinea‐Bissau. Social Anthropology 25(3), 364-379.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1469-8676.12418

126. Mullin, M. 2002. Animals and anthropology. Society and Animals 10(4):387-394.

https://www.animalsandsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/mullin.pdf

127. Nance, S. and Colby, J. (2015). The Historical Animal. New York: Syracuse University Press.

128. Trautmann, T. R. 2015. Elephants and Kings: An Environmental History. University of Chicago Press.

129. Cohen, D. W., & Odhiambo, E. A. (1989). Siaya: the historical anthropology of an African landscape. East African Publishers.

130. Haraway, D. J. (2008). When species meet, 224. University of Minnesota Press.

http://xenopraxis.net/readings/haraway_species.pdf

131. Johnston, C. (2008). Beyond the clearing: towards a dwelt animal geography. Progress in human geography 32(5), 633-649.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0309132508089825

132. Wolch, J. & Emel, J. (1995). Bringing the animals back in. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 13(6), 632–6.

https://journals.sagepub.com/toc/epd/13/6

133. Tsing, A. (2012). Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species: For Donna Haraway. Environmental humanities 1.1: 141-154.

https://read.dukeupress.edu/environmental-humanities/article/1/1/141/8082/Unruly-Edges-Mushrooms-as-Companion-SpeciesFor

https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/10618/1/sousa_frazao-moreira_2010.pdf

125. Sousa, J., Hill, C. M. & Ainslie. A. (2017). Chimpanzees, sorcery and contestation in a protected area in Guinea‐Bissau. Social Anthropology 25(3), 364-379.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1469-8676.12418

126. Mullin, M. 2002. Animals and anthropology. Society and Animals 10(4):387-394.

https://www.animalsandsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/mullin.pdf

127. Nance, S. and Colby, J. (2015). The Historical Animal. New York: Syracuse University Press.

128. Trautmann, T. R. 2015. Elephants and Kings: An Environmental History. University of Chicago Press.

129. Cohen, D. W., & Odhiambo, E. A. (1989). Siaya: the historical anthropology of an African landscape. East African Publishers.

130. Haraway, D. J. (2008). When species meet, 224. University of Minnesota Press.

http://xenopraxis.net/readings/haraway_species.pdf

131. Johnston, C. (2008). Beyond the clearing: towards a dwelt animal geography. Progress in human geography 32(5), 633-649.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0309132508089825

132. Wolch, J. & Emel, J. (1995). Bringing the animals back in. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 13(6), 632–6.

https://journals.sagepub.com/toc/epd/13/6

133. Tsing, A. (2012). Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species: For Donna Haraway. Environmental humanities 1.1: 141-154.

https://read.dukeupress.edu/environmental-humanities/article/1/1/141/8082/Unruly-Edges-Mushrooms-as-Companion-SpeciesFor

This database was created in the scope of the post-doctoral fellowship of Dr Hannah E. Parathian (CRIA/04038/BPD/DASE) financed by FCT (UID/ANT/04038/2013). Funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia I.P., in the scope of CRIA's strategic plan (UIDB/04038/2020).

Citation: Parathian, H. & Frazão-Moreira, A. (2022) People, Culture & Conservation in West Africa: Studies of Multispecies Coexistence. Online Database. CRIA (Centre for Research in Anthropology).

© 2022 Hannah Parathian & Amélia Frazão Moreira. All rights reserved / Credits and privacy policy.

Citation: Parathian, H. & Frazão-Moreira, A. (2022) People, Culture & Conservation in West Africa: Studies of Multispecies Coexistence. Online Database. CRIA (Centre for Research in Anthropology).

© 2022 Hannah Parathian & Amélia Frazão Moreira. All rights reserved / Credits and privacy policy.